Fossil evidence

The fossil record provides snapshots of the past which, when assembled, illustrate a panorama of evolutionary change over the past 3.5 billion years. The picture may be smudged in places and has bits missing, but fossil evidence clearly shows that life is very, very old and has changed over time through evolution.

Early fossil discoveries

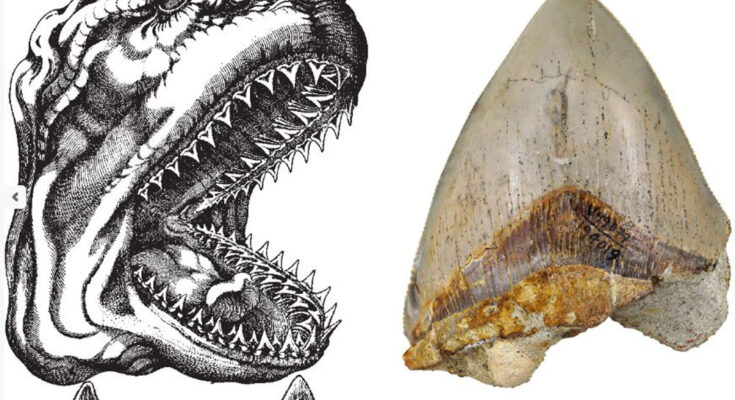

Scientists have long recognized fossils as evidence of past life. The ancient Greek philosopher Xenophanes found fossilized shells on dry land and concluded that the area had once been a seabed. Almost a thousand years ago, the Chinese scientist Shen Kuo made similar arguments based on fossilized remains from species that could not have lived the modern environments in which they were discovered. In the 17th century, Nicholas Steno noted the similarity between shark teeth and the rocks commonly known as “tongue stones,” making the argument that the stones had come from the mouths of once-living sharks. Since then, paleontologists such as Victorian England’s Mary Anning, who helped uncover the first correctly identified ichthyosaur fossil, have continued to flesh out our understanding of the diversity of ancient life forms.

Additional clues from fossils

Today, few question the finding that fossils represent past life. It’s hard to look at a T. rex skeleton and conclude otherwise. But this doesn’t mean that science is done with fossils. Paleontologists continue to learn from fossils – and not just about the anatomy of the organisms preserved.

Fossils reveal ecological relationships from the past

This leaf fossil (which is a bit more than 10 million years old) shows a distinct pattern of damage – one that matches the damage to modern leaves caused by the caterpillar of the moth Stigmella heteromelis. The damage patterns are so similar and distinct from other sorts of leaf damage that, although we don’t have fossils of the ancient moth itself, we know from the leaf fossil that it must have been present in the environment and at the time that this plant lived. Based on where this fossil was found, scientists know that the moth species has a much smaller range today than it did in the past. The fossil also reveals that this caterpillar was parasitized by a tiny wasp, as indicated by the small circular hole (yellow arrow) made by the wasp as it exited. We observe the same parasitic relationship between wasps and S. heteromelis today.

Fossils, physiology, and behavior

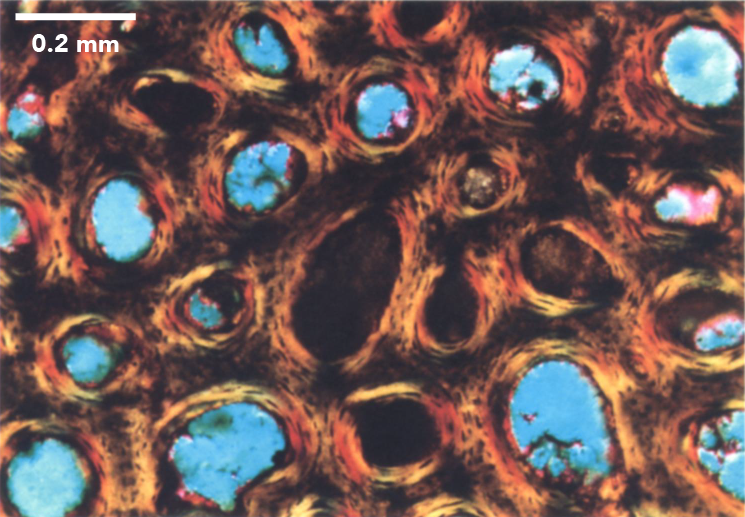

Fossils can also tell us about growth patterns in ancient animals. For example, this picture shows a cross-section through the skull of the dome-headed dinosaur Stegoceras validum. The blue spaces show where blood vessels ran through the bone. The density of blood vessels on the dome indicate that this bone was growing quickly. That, along with other lines of evidence, suggest that this fossil came from a juvenile. In fact, the dome-head of this dinosaur species was at its most extreme in juveniles. This (again, along with other evidence relating to the strength of the dome) suggest that the dome was not used in head-butting competitions for adult mates, and probably served some other function – perhaps helping individuals of the same species recognize one another.